o

Metadata

- Author: Sangeet Paul Choudary

- Full Title: Don’t Sell Shovels, Sell Treasure Maps

- URL: https://platforms.substack.com/p/dont-sell-shovels-sell-treasure-maps

Highlights

- In 1849, a swarm of men poured into California, lured by rumours of rivers filled with gold. This was the Gold Rush, where everyone rushed toward the same valleys and set up camp beside the same creeks. All drunk on the same hype. All nodding in unison to create consensus theatre. The smarter ones didn’t dig at all. They sold shovels instead. Somehow, that’s the metaphor that stays on every time we talk about a gold rush. In a gold rush, they say, don’t dig for gold. Sell shovels instead. But what if we’re getting our gold rush metaphors not quite right? (View Highlight)

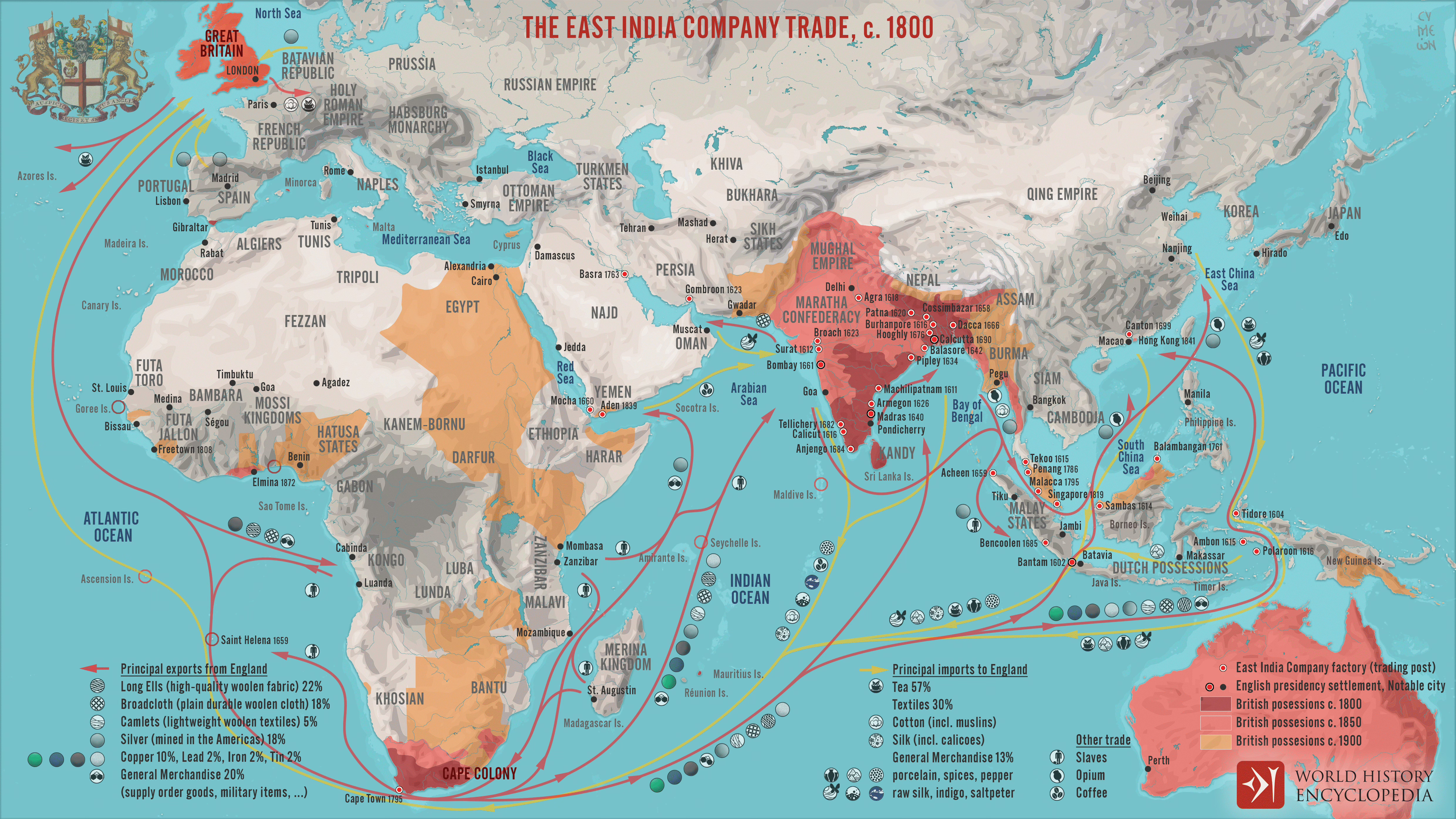

- The British East India Company may not have carried shovels, but it was, in every strategic sense, a gold digger. While others dug for gold, the Company hunted for extractive advantage. It looked for control over trade routes and monopolies on spices, tea, and textiles. It looked for the ability to tax and govern without formal sovereignty. Why dig through dirt when you could redirect the flow of wealth by owning key control points: the ports, the ships, the legal systems. The world which the Company set to control and conquer was poorly mapped. Most European fleets relied on intuition and seasonal memory to navigate the seas. But the East India Company was a gold-digger with a plan. It began to map global wind patterns and ocean currents methodically, to create wind charts, sailing calendars, and routing logic, which saved months on their journeys and reduced shipwrecks. Instead of bothering with gold and shovels, or even with building better ships, the Company was focused on building maps. Better maps create better strategies for movement. (View Highlight)

- In fact, mapping didn’t stop at mapping the seas. Mapping India, the Company’s prime gold-digging target, was its most powerful act of conquest. The Great Trigonometrical Survey of India transformed a complex network of locally governed kingdoms into something that could be centrally governed from London. Maps helped the Company convert a decentralized and fragmented system of landholding and agriculture into standardized, taxable units. Mapping was governance. And mapping, more importantly, was scalable extraction. Once the land could be standardized, it could be governed and taxed. The Company knew that the key to a gold rush was not so much in better shovels as it was in better maps. Maps could help locate concentrated value and help the Company insert itself at the point of control. (View Highlight)

- The Company used maps instead of shovels. But they were incredibly effective at extracting value. That’s because in systems defined by uncertainty and competition, better shovels - or superior tools - are irrelevant. What matters far more is knowing where to dig. Most enterprise AI providers are selling shovels today. Tools that promise to execute familiar tasks faster. Generate presentations and contracts faster. Sell a thousand personalized emails. (View Highlight)

- The real opportunity lies elsewhere, though. Better execution is good in a stable environment, but in an environment with structural uncertainty, what you. need is better navigation. Traditional enterprise software is built on the idea of workflow automation. The assumption is that the workflow itself makes sense, the bottleneck is execution. AI is sold into enterprises today with a similar productivity-first framing. Do more of what you already do in less time with fewer people. It makes for easy demos and shorter procurement cycles. But it’s also a trap. When everyone is improving the same workflows at the same speed, the gains become incremental and there is no differentiation or advantage. (View Highlight)

- Margins go down. and you end up in a commodity race, as the productivity gains paradox sets in. Every competitor has access to the same tools and the same automation. The only way to compete is by lowering cost or increasing volume. It’s the enterprise version of the vibe-coding paradox. (View Highlight)

- Shovels sell speed. Treasure maps sell direction. And whenever a technology positions itself as a way to reduce uncertainty and unlock hidden opportunities, and most importantly, change the basis of competition, it moves from creating mere efficiency to creating leverage. These solutions command higher margins because they create asymmetric value in ways that others can’t easily copy. (View Highlight)

- AI lends itself naturally to treasure maps. It has the capacity to uncover hidden relationships across fragmented datasets. Intelligent solutions can detect small shifts before they escalate and surface weak signals that might otherwise go unnoticed. (View Highlight)

- Yet, we continue to package AI solutions like traditional productivity software. Just another way to crank out more of the same work. The value of AI is in showing us what we should be doing differently, not in helping us do more of what we already do.

Most enterprise AI providers miss this - partly for lack of imagination, and partly blinded by hype.

A shovel mindset treats AI as a way to reduce costs

A treasure map mindset treats AI as a way to make better decisions. (View Highlight)

- The shovel mindset drives marginal improvements. The treasure map mindset helps you reimagine workflows and organizational structures. The rise of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) created this divergence among manufacturers in the 1990s. Most firms initially adopted it with a shovel mindset. They swapped out pencil-and-paper drafting for digital drawing. This made individual designers more productive as they could easily generate and edit blueprints. But the underlying workflows remained the same. Boeing, on the other hand, approached CAD/CAM with a treasure map mindset. Instead of digitizing drafting alone, they used CAD to integrate the workflow across design, manufacturing, simulation, and assembly. With CAD, they could prototype entire aircraft virtually and detect component clashes in advance. This helped better coordinate the workflow across engineering, production, and supply chain. (View Highlight)

- Better and more integrated workflows are interesting, but they’re only a starting point. Treasure maps are more interesting when they help you dig where no one has dug before, and with that, they change the very basis of competition. (View Highlight)

- Think of TikTok, a late entrant into social networking, shifting the basis of competition using AI. Unlike Facebook or Instagram, which were structured around known-user social graphs, TikTok redefined the basis of competition through AI-powered content discovery. It shifted the attention model from who you know to what you engage with, forcing every social platform to rethink its core mechanics. Shovel AI helps you do what you already do, but more cheaply. Treasure map AI helps you see what you should be doing instead, and redesign your workflows, organization, and business model accordingly. Even the way companies adopt AI reflects this. (View Highlight)

- If your company’s basis of competition remains unchanged with or without AI, you are not really AI-native. (View Highlight)

- Selling shovels is easy but commoditized. Everyone’s selling speed. Everyone’s pitching cost reduction. Selling treasure maps is a harder sale, but once you’re in, you’re harder to displace. (View Highlight)

- If you’re selling a treasure map, you’re facilitating a conversation. You’re in the room with someone who owns risk, or growth, or transformation. You’re focused less on demoing product features and more on helping answer the question What’s happening in your business that you can’t yet see? That conversation is no longer ticking a procurement checklist. Once implemented, every decision made and every pattern identified by the ‘treasure map’ gets you codified deeper in the enterprise. You start building a growing proprietary graph that reflects how the organization thinks and moves, and eventually, how it competes. Ripping that out of the organization is non-trivial. (View Highlight)